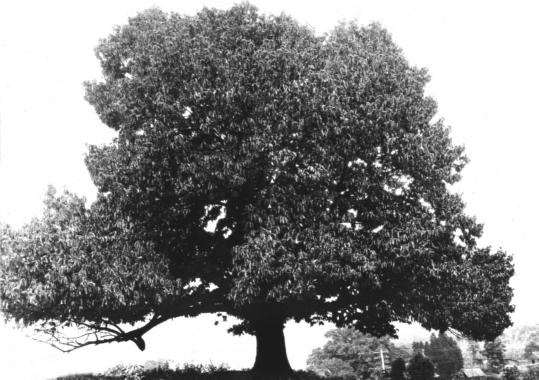

The American Chestnut is a large, stately, useful tree. At one time, over a quarter of the eastern American woods were populated by this tree. The wood is rot resistant, the nuts are delicious, and even the oils in its bark has medicinal properties.

The American Chestnut is a large, stately, useful tree. At one time, over a quarter of the eastern American woods were populated by this tree. The wood is rot resistant, the nuts are delicious, and even the oils in its bark has medicinal properties.

Nobody wanted to see the Chestnut go away, and it didn’t want to die off. Over eons it evolved into the strong, prolific queen of the forest. It provided shade, shelter, and nourishment for the rest of the woods, and it provided it’s resources for the native Americans and settlers in the areas in which it grew.

But it got a raw deal.

In the early 1900’s, the Chestnut blight found it’s way across the ocean. At first, it slowly spread and weakened the population, but within 30 years, nearly every single Chestnut tree had been wiped out. It fought like hell to survive, all the while still providing resources to all, but ultimately, it succumbed to the blight.

There’s a legacy all around from this tree. 300 year old cabins, deep in Appalachian hollows made of chestnut logs still stand without so much as a scratch. Fence posts randomly stand along old farm fields, silently reminding us of how important this tree once was. It’s been gone for years, but there are still people living from the bounties that this tree provided.

It’s a tree. It didn’t have the choice to run away from the blight. It couldn’t magically evolve in 30 years’ time to be resistant to the disease that would take it. While other trees just continued growing all around it, it proudly lived out it’s days without complaint until the day came when the fungus took hold, and it died an honorable death.

Even still, old stumps from these fallen majesties throw up new shoots. You can still find a few mature American Chestnuts in spots where the fungus either never spread, or where it wasn’t as severe. There are people working tirelessly to bring this tree back from total annihilation, researching ways to stop the disease. There is hope that one day, the Chestnut will once again be able to live a normal, content life in the forest, without outside intervention.

But if and when those people succeed, that doesn’t bring the trees that already died back. Those trees can do nothing but leave a legacy. They can continue to exist as shelter from storms, or safe spaces for loved ones in the form of four walls. They cannot grow or amend that legacy, they can only exist in a state of either satisfaction with their life’s work, or disappointment in what they didn’t get to become.

If you’ve read this far in my ramblings about a tree, I hope that you realize that Megan, and the disease she had are so much like the American Chestnut. She grew as long as she could. She provided shelter and safety without fail, all along knowing that someday, the time would come where a blight she didn’t ask for would take her. Shelby dropped from her limbs and began growing herself, all the while with her mother watching over her proudly as long as she could. When she finally fell from her disease, she provided nutrients to the immature tree that she spawned.

There are still reminders of her everywhere. Little signs that she was once the queen of our forest. Events come and go each year, and Shelby both grows like her mother, yet evolves slightly to throw up her new shoots. There are researchers working tirelessly to cure or remove Cystic Fibrosis as a threat, and though I hope with all of my heart that they succeed, it will never bring those back that have already succumbed.

Though Megan’s favorite tree was a Willow, mine is the American Chestnut. I can always hold hope that it will come back someday, but I have to be happy that it ever even existed to provide so much for so many.