20 years ago, I woke up to a screaming drill instructor, chaos, mind games, and effectively running everywhere I went. I lived in a green uniform, seeing no other colors but black, green, and brown for months. I swam in 10 foot deep water with 120 pounds of gear, went 3 days and 48 miles of marching on 4 hours of total sleep (and one meal). I didn’t speak with my family for 13 weeks, other than the occasional letter. I ran until I died, and then ran some more. Rifle marksmanship, hand-to-hand combat, history, military legal codes, uniform standard, rappelling, gas chambers, and a multitude of other subjects were drilled into my head, non-stop, and if I should not be sufficient in any given one, I would be held back and given another week on that godforsaken island in South Carolina.

Marine Corps recruit training (boot camp) was the hardest thing I had ever done, and for a long time, I thought it would be the hardest thing I would ever do.

If it was, I wouldn’t be writing to you today.

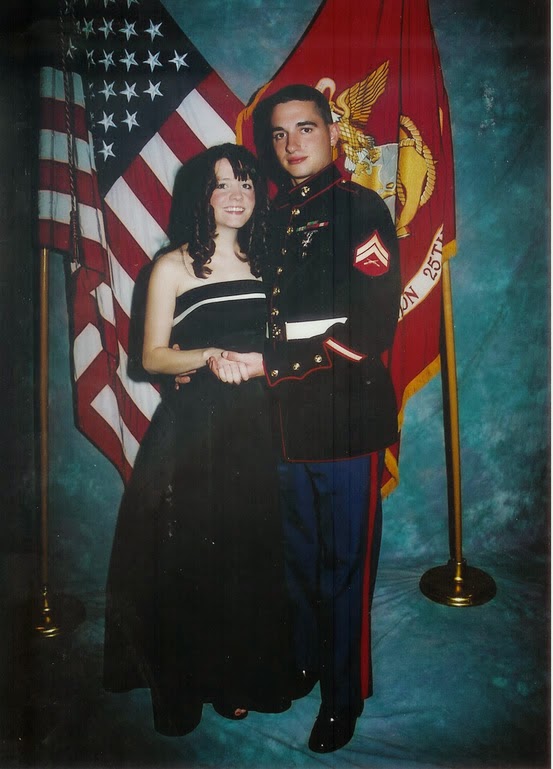

As luck would have it, becoming a Marine was indeed the hardest thing I had ever done, and my most prideful accomplishment for long after my service had ended. Granted, I knew what was coming when I enlisted. I knew the training schedule, the history, the reputation, and the basics of what was going to happen. I knew when I would be entering the “fleet”, what my role would be, and the exact date of my discharge. I mentally, and physically was able to prepare myself leading up to the date I shipped to Parris Island, leaving my family and everything I knew behind in Ohio to go on this new adventure.

I served for 6 years, 4 on active duty, meeting Megan around the middle of year 5, when I was a reservist. Here presented to me, was a new challenge. She informed me of her condition on our first date. When I asked about a second, she hesitantly said she was being admitted to the hospital, and had to politely decline.

For one reason or another, I didn’t see that as a hindrance. I was intrigued by her regardless, and her having a condition that required hospitalization a few times a year would be no big deal for me, having been deployed 6 months out of any given year.

I realize now, that unlike the Marine Corps, I wasn’t given a choice to move forward with Megan. I couldn’t quit at any time in the infancy of our relationship, lest I live in constant regret. Fate, rather than free-will, brought us together. As our relationship built, I learned more and more about what I would be a part of, and how difficult it would be, and I marched on unflinchingly. I was drafted into being her boyfriend, fiance, and then husband, whether I wanted to or not. The was no “oath of enlistment”. No ceremonial moments denoting milestones. No ribbons or medals were awarded to service above and beyond the call of duty. Promotion and rank in our relationship was a simple matter of changing titles, with no extra pay, authority, prestige, or responsibility.

I had seen friends die while I was in the Marines. I grieved, of course, but at the same time, there was a sense of honor. They volunteered to be a part of the military. They put in all of the work and determination it took to earn their titles. They sacrificed everything for something they believed in, knowing the risks were great, rewards were intangible and few, and they had choice at the root of the matter.

Megan didn’t have choice. There was, quite literally, nothing she could do but prolong the inevitable. She knew, with almost surety, how she was going to die, and roughly when. The story of Cystic Fibrosis had played out time and again in front of her. Her best friends shared her disease, like an esprit de corps that none of them wanted to partake in, but did nonetheless. She watched friends die, her own brother even, without the sense of honor that I got to attribute to death. At least yearly, a friend would pass away lying in a hospital bed, surrounded by family, after wasting away and not being able to breathe on their own for months.

I didn’t share this bond with her friends. I was healthy and physically a functioning adult. I never knew what it was like to not be able to breathe easily for years, other than 30 minutes in a teargas chamber here and there. I never experienced what it would be like to not be able to have children, or even worse, knowing we could, but shouldn’t. I was an outsider, there to love and take care of my family through all of it, while never actually having to experience it in my own body.

But I experienced it in my soul. When Megan was sick, my heart was sick. When she couldn’t get out of bed, physically, I would carry her downstairs, ensure she was as comfortable as could be, and subconsciously grieve. I never realized it at the time. It presented itself as grumpiness outwardly, but inside, I was sad for yet another loss of function.

I was mourning her death for years, while still doing my best to be a good husband, father, and provider.

And that is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.