We’re moving.

We’re moving.

September 16 the packers come.

September 17 they take it all and move it to our new digs.

I’ve been clearing out,

getting rid of stuff,

And

bumping into him.

On Thursday, the kids and I emptied out his closet.

He had his own closet.

It was such a tiny thing for such a big man. (6’6″)

At four months, I got rid of all the clothes of his that

I didn’t like

plus

the ones on his side of the dresser.

In death, I rejoiced in the small pleasure of having extra space.

But the clothes I loved,

the clothes that meant something to me,

the ones I kept thinking that he would walk back into the house wearing,

those I kept.

A suit, his navy jacket,

the many favored t-shirts,

7 pairs of his size 14 shoes — the black Chuck Taylors, the Kenneth Coles and the LL Bean slippers.

His smelly red cycling jacket,

his UVA cap and the shirt and tie my grandmother bought for him.

I kept them all,

trusting that “they” would be right,

I would know when it was time to shed his belongings.

“Tonight,” I said to the kids,

“Tonight we need to go through Daddy’s clothes. You can each pick out a few pieces that I will put away for you but the rest will go to the Los Angeles Men’s shelter downtown.”

Just before we started, I warned “This may bring up a lot of feelings. That’s a good thing. If you feel sad, it’s good. If you don’t, it’s good. Just remember, the grief will not hurt you permanently. I know you know this but I want to remind you that it will feel like the world is ending but it’s not. They are just feelings. All feelings pass.” I used my most gently mom voice.

Then we go to work.

The result is his closet now looks like this.

A few days before, I was squatting in front of the black credenza by the front door.

I peered in to see what was on the shelf.

And there it was.

His medical notebook.

The second notebook that detailed all his medical procedures,

drug cards with their ominous side effect warnings

everything is there except…

the fact that he was dying.

I go through the notebook, remembering names like adriamycin and neutrapenic. I find the tickets from the blood drive held at his school. When I go into Cedars blood donation center a week after the drive, to collect those tickets, the head of the center stops me. “Who is Art Nagle?” My husband I said. “Well he is one hell of man. In my 15 years of doing blood drives I have never seen such an outpouring of love. He’s touched many people.”

I’m holding those tickets in my hand now and smiling, remembering that in a way she saw more of him than I did.

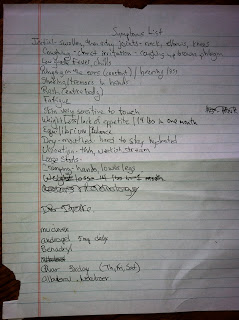

Behind the tickets is a piece of paper.

It has his handwriting on it.

It is a list of all his symptoms before

we knew it was cancer.

I stare at the list

angry at our stupidity.

“Honey, just write down all your symptoms. It’ll be easier than trying to remember it.” I told him.

The list was from the second time he had cancer. I know this because he wrote “loose stools.” A stoic man from Maine would never write “loose stools” had he not already understood that in illness, your body is not yours.

I can’t take my eyes off the list.

I read it over and over and over again.

As I lay it down in the keep pile, I want to smack myself, to punch myself in the face for being so fucking stupid, for not recognizing the signs of the cancer … again. For not believing that lightning can strike twice.

Like it would have helped.

Nothing helps. He’s gone. I’m here.

Even in our new place, I see that death has taken away my ability for a

clean,

fresh

landing.

There is no such thing.