My mind and heart feel a bit scattered, this week. I have returned from retreat to work and errands and the ups and downs that characterise life in the real world. Each time I go on a retreat, I want to stay there, where there is space and quiet and a relief from worry about finances and obligations and commuting and cleaning and all the things that we resist and resent. But I know that living the life of a monk or a hermit is not my path, however appealing it seems, at times. So I return, and try to juggle the mundane tasks of life in western society with the contemplative life that calls to me.

I am facing some possible changes at work, where there are huge budget cuts expected, in the next two years, which could mean that the program I am managing will end. This means more changes in my work life, and, though I don’t have a lot of fear around finding a job (there are always jobs in the field of child abuse and neglect, unfortunately), I am not ecstatic about the prospect of having to acclimate to a new work environment. I would prefer to move from this position to retirement, but I am fortunate to even have a job, in these economic times, and for that I am grateful.

My husband’s granddaughter is headed toward University today, and we all gathered at his daughter’s house, on Friday, to send her off and wish her well. I felt Stan’s presence all around us. I could picture him, sitting on the sofa, in his usual spot, at his daughter’s house, beaming with pride, with me there, right beside him. We were all mindful of his physical absence, that night, as we raised our glasses in toast to her, and to her accomplishments.

My nephew is coming for a short visit, today. He grew up in Indiana, and now lives in Denver, and loves hiking and rocks, having studied geology, so I hope to show him some of our beautiful countryside while he is here. He lost his older brother, who died at the age of 23, in 2004. Eleven years ago. Chris’ death was a shock to us all, a devastating loss for our family, and for his father, him, and his sister, especially. It is hard to believe that someone can die so very young. I am mindful of this loss, and of the hole it left in all of our lives, as I ponder going to meet my nephew at the train station this afternoon.

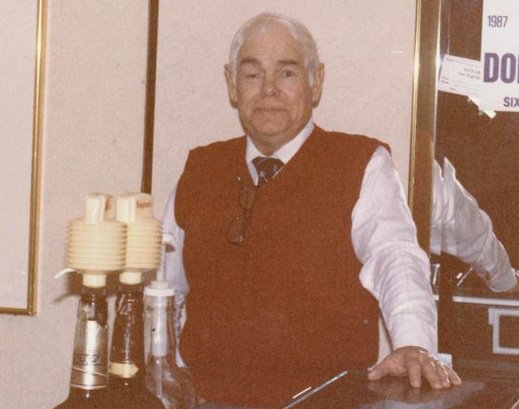

And I am remembering my father, today. He died on the 1st of October in 1987. 28 years ago. He was 62. I remember, then, thinking that he was old, not old enough to die, but that he had lived a life that was long and full. Now, at the age of 58, I see how very young 62 is. He missed out on so much of our lives, and of his. He always talked about wanting to live to see the year 2000. He didn’t get to do that. He didn’t get to meet my son, a boy he would have loved and celebrated and with whom he would have found great commonality.

It feels strange, sometimes, to think back to the days when my dad was alive. I was so close to him, and I relied on him for his wisdom and knowing and for his emotional support when I was struggling with the dramas that we create for ourselves in adolescence and early adulthood. He always knew the right words to say to help me get a perspective on my often self-imposed suffering. He understood what was important in life, and he tried to help me see it.

I remember accompanying him to a radiation treatment when he was fighting lung cancer, in the summer of 1986. Watching him take off his shirt and lie under that big machine, I saw him as vulnerable for the first time in my life. His body looked so small and frail. I knew, in that moment, that it would only be a matter of time before he left us, and the thought of losing him was almost too much for my heart to bear.

We didn’t get that time to ponder the loss of my husband. He died at the age of 63, and witnessing his sudden death was a trauma of its own that has complicated our grief journeys. One moment, his strong presence was a source of comfort and solace for us, and the next moment, he was gone.

Sometimes, I feel overwhelmed by all these pockets of loss.

When I was on retreat, I walked, most mornings, to the old church down the road, and strolled amongst the graves of the people who once lived in the village nearby. I love graveyards. I am a storyteller, and I love to read the short stories of peoples’ lives and deaths, etched so poignantly into the stone.

There were graves of infants and children, of brothers and sisters, and graves of husbands who died, and their wives, buried next to them, twenty years later. At the turn of the century, five children fell through broken ice on a pond near the village, and all of them drowned. Each day, I would trace my finger along the names of those children. Eight years old. Ten years old. Nineteen. Sixteen. Twenty.

I found comfort there, sitting among the graves. It helped me, not to minimise my losses, or discount them, but to remember that others had experienced so much loss, too. It helped me to remember that loss is inevitable, and that the only way to protect ourselves from it is to hide from love, and from life, to harden, to build a wall between ourselves and others, to shrivel up inside.

As painful as I find them, these pockets of loss are important, and necessary. They mean that I am still soft, and alive, and that my heart remains open to the world that unfolds around me.

There is so much pain. And so much beauty.

As much as it hurts, I am grateful for these pockets of loss. I am grateful to have known my dad, so full of humour and wisdom, to have known my nephew, that chubby, ginger haired boy, to have lived all those years with my mother, my sister, my sister in law. To have known Gavin, Stan’s son, who died two weeks before Stan. To have lived those short, sweet, three years with my husband.

To have known him. To have known them all.

To have loved.